Visual Evoked Potential (VEP)

- What is a visual evoked potential (VEP)?

- When is the VEP used?

- What does the VEP detect?

- How to prepare for a VEP test

- What happens during a VEP test?

- Side effects

- Factors influencing VEP

- What the results of the VEP may show

- Clinical usefulness of the VEP

- Summary of VEPs

What is a visual evoked potential? (VEP)

A visual evoked potential is an evoked potential caused by a visual stimulus, such as an alternating checkerboard pattern on a computer screen. Responses are recorded from electrodes that are placed on the back of your head and are observed as a reading on an electroencephalogram (EEG). These responses usually originate from the occipital cortex, the area of the brain involved in receiving and interpreting visual signals.

A visual evoked potential is an evoked potential caused by a visual stimulus, such as an alternating checkerboard pattern on a computer screen. Responses are recorded from electrodes that are placed on the back of your head and are observed as a reading on an electroencephalogram (EEG). These responses usually originate from the occipital cortex, the area of the brain involved in receiving and interpreting visual signals.

When is the VEP used?

A doctor may recommend that you go for a VEP test when you are experiencing changes in your vision that can be due to problems along the pathways of certain nerves. Some of these symptoms may include:

- Loss of vision (this can be painful or non-painful);

- Double vision;

- Blurred vision;

- Flashing lights;

- Alterations in colour vision; or

- Weakness of the eyes, arms or legs.

These changes are often too subtle or not easily detected on clinical examination in the doctor’s surgery. In general terms, the test is useful for detecting optic nerve problems. This nerve helps transfer signals to allow us to see, so testing the nerve allows the doctor to see how your visual system responds to light. The test is also useful because it can be used to check vision in children and adults who are unable to read eye charts.

What does the VEP detect?

The VEP measures the time that it takes for a visual stimulus to travel from the eye to the occipital cortex. It can give the doctor an idea of whether the nerve pathways are abnormal in any way. For example, in multiple sclerosis, the insulating layer around nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord (known as the myelin sheath) can be affected. This means that it takes a longer time for electrical signals to be conducted from the eyes, resulting in an abnormal VEP. A normal VEP can be fairly sensitive in excluding a lesion of the optic nerve, along its pathways in the anterior part of the brain.

How to prepare for a VEP test

You will be given instructions on how to prepare for the test. This will depend on where you are going to get the test done. Some things that you may need to do include:

- Washing your hair the night before, but avoiding hair chemicals, oils and lotions.

- Making sure you get plenty of sleep the night before.

- If you wear glasses, make sure you bring these along with you to the test.

- You are usually able to eat a normal meal and take your usual medications prior to the test. However any medications that may make you drowsy should be avoided.

- Arrive on time and try to relax before the test.

- On the day of the test, you should also let the technician know if you have any eye conditions such as cataracts or glaucoma as this can affect the test and should be noted in your records by the doctor.

What happens during a VEP test?

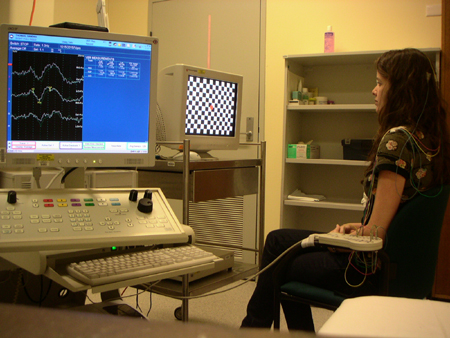

|

| (Image courtesy of Dr K Ng) |

The procedure is very safe and non-invasive.

- Firstly, some wires will be glued to the top of your head to detect the brain waves.

- A technician will give you further instructions on what to do during the test. Normally, each eye will be tested separately.

- It is very important that you co-operate with the technician who conducts the test and be able to fix your vision in a certain spot. You will be asked to look at a screen similar to a television screen, with various visual patterns.

- Readings will be recorded through the wires on top of your head.

- After the procedure, the glue and wires are removed from your head. The doctor may discuss the results of the test with you after they have been analysed; otherwise the referring doctor will.

- Usually the procedure takes about 45 minutes.

Side effects

There are rarely any side effects from this procedure. It is a painless procedure and apart from possible minor skin irritation from the electrodes, there are often no complications. If you have any medical conditions such as epilepsy, the visual stimuli you are exposed to is unlikely to set off seizure activity. This should however be noted with your doctor and technician before you undergo a VEP test.

There are rarely any side effects from this procedure. It is a painless procedure and apart from possible minor skin irritation from the electrodes, there are often no complications. If you have any medical conditions such as epilepsy, the visual stimuli you are exposed to is unlikely to set off seizure activity. This should however be noted with your doctor and technician before you undergo a VEP test.

After the procedure is done, patients normally return home on the same day. You should be able to drive home safely if you are feeling well after the procedure.

Factors influencing VEP

The cells within the part of your brain involved with vision are most sensitive to movement at the edges of your central visual fields. If you have poor vision, this does not seem to have too much effect on the response – larger checkerboard patterns can be used. Your gender, age and the size of your pupils are other factors that can affect the VEP. If you have taken any drugs that make you drowsy, or under the influence of any anaesthetic drugs, your VEP is also greatly affected.

What the results of the VEP may show

The VEP is particularly useful in detecting past optic neuritis. This refers to inflammation of the optic nerve, associated with swelling and progressive destruction of the sheath covering the nerve, and sometimes the nerve cable. As the nerve sheath is damaged, the time it takes for electrical signals to be conducted to the eyes is prolonged, resulting in an abnormal VEP. This may be seen in multiple sclerosis – one of the most common causes of optic neuritis (as above). Abnormal VEP’s are seen in multiple sclerosis patients due to the presence of optic neuritis.

The following are less easily differentiated but may cause abnormal VEPs:

- Optic neuropathy – this can be due to damage of the optic nerve from a number of causes, including: a blockage of the nerve’s blood supply, nutritional deficiencies, or toxins. As the nerve is damaged, electrical signals do not conduct properly. Examples include diabetes in the advanced stages which can be associated with damage to the blood vessels and nerves supplying the eyes, or toxic amblyopia which is a condition of the eyes associated with decreased vision, due to a toxic reaction in part of the optic nerve.

- Tumours or lesions compressing the optic nerve – if the optic nerve is compressed, the pathway for conduction is affected and an abnormal VEP is seen.

- Glaucoma – patients who suffer from glaucoma have increased intraocular pressure (ie pressure inside the eye). This can result in damage to the optic nerve, leading to prolonged VEPs.

- Ocular hypertension (high pressure) – this refers to any situation in which the pressure in the eye is higher than normal. There are no signs of glaucoma, but patients may be at increased risk of developing glaucoma later in life.

Clinical usefulness of the VEP

The VEP is a standardised and reproducible test of optic nerve function

The VEP is a standardised and reproducible test of optic nerve function- It is more sensitive compared to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in detecting lesions affecting the visual pathway in front of the optic chiasm (area in the optic pathway where the optic nerve crosses sides)

- It is usually less costly compared to other investigations such as MRI

- If results of the VEP are negative, this can be useful in excluding certain disorders.

Summary

The VEP is an important test that is very good at detecting problems with the optic nerve and lesions in the anterior part of our visual pathway, before the optic nerves merge. However, it is a non-specific test and to determine the exact underlying problem in each patient, a good history and examination is also very important.

Article kindly reviewed by:

Associate Professor Karl Ng MB BS (Hons I) FRCP FRACP PhD CCT Clinical Neurophysiology (UK) Consultant Neurologist – Sydney North Neurology and Neurophysiology (download referral form and map); Conjoint Associate Professor – Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney; and Editorial Advisory Board Member of the Virtual Neuro Centre.

References

- Ropper AH, Brown RH. Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology (8th edition). McGraw-Hill; 2005.

- Atilla H, Tekeli O, Ornek K, et al. Pattern electroretinography and visual evoked potentials in optic nerve diseases. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13(1):55-9. [Abstract]

- Huszar L. Clinical utility of evoked potentials [online]. E-medicine. 2006 [cited 31st July 2007]. Available from: [URL link]

- Warrell DA, Cox TM, Firth JD (eds). Oxford Textbook of Medicine (4th edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- Misulis KE, Fakhoury T. Spehlmann’s Evoked Potential Primer (3rd edition). Butterworth-Heinemann; 2001.

- Fuller G, Bone I (eds). Neurophysiology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005:76 Suppl 2:ii1-46. [Abstract | Full text]

- Nuwer, MR. Fundamentals of evoked potentials and common clinical applications today. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;106(2):142-8. [Abstract]

- Odom JV, Bach M, Barber C, et al. Visual evoked potentials standard (2004). Doc Ophthalmol. 2004;108(2):115-23. [Abstract]

- Deuschl G, Eisen A (eds). Recommendations for the Practice of Clinical Neurophysiology: Guidelines of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl. 1999;52:1-304. [Abstract]

Dates

Tags

Created by:

Login

Login