How to save your vision the high-tech way

Our eyes are truly amazing pieces of hardware, far superior to any camera lens. Two separate eyeballs make precisely synchronised movements thousands of times a day, while tiny adjustments in the shape of our lens keep the world in perfect focus. Eyes are fully developed by age 7, can last 100 years and require roughly 20 blinks a minute to keep them clean.

Eyes on the prize

We know it’s not unusual to lose a little visual precision with age, but it’s nothing that a pair of reading glasses can’t fix. More worrying are the diseases that can cause sudden, irreversible damage to the delicate tissues of the eye.

The macula is a tiny spot on the retina that is responsible for all of our central, high-acuity vision. Any damage to the macula can throw our visual world into a permanent shadow.

|

For more information about the different parts of the eye and what they do, see The Eye and Vision. |

Diabetes

It’s no secret that diabetes is on the rise in Australia. What’s not as well known is the increase in diabetic eye disease or “diabetic retinopathy”.1 Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide.2 Over 15% of Australians with type 1 or type 2 diabetes have diabetic retinopathy.2

Diabetes can cause tiny blood vessels in the eye to weaken or burst, damaging nearby tissue. In advanced stages of diabetic retinopathy, the eye tries to grow new retinal blood vessels (called proliferative diabetic retinopathy), but these can also bleed and cause further damage.1

If any of these new blood vessels are leaking blood into the macula, the macula can become swollen (macular oedema) and loss of vision can occur very quickly.3

| For more information about the risk factors for diabetes and how they can be minimised, see Diabetes. |

Macular Degeneration

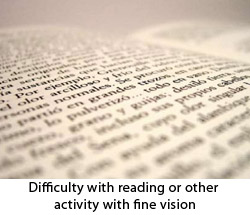

Another common and worrying eye condition is macular degeneration.4 In Australia, nearly 50,000 people have low vision due to age-related macular degeneration.5 Most cases of macular degeneration progress slowly; aging blood vessels in the macula start to deteriorate and vision slowly worsens. Patients with “dry” macular degeneration may complain of trouble with reading, writing and driving.11

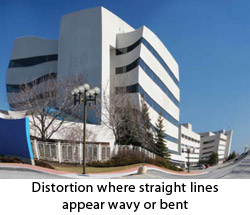

What’s much more concerning is the aggressive form of the disease, or “wet” macular degeneration (also known as neovascular or exudative macular degeneration).4 As blood vessels weaken, new blood vessels grow to take their place under the macula. These new vessels can burst, releasing blood and causing irreparable damage to the macula. Left untreated, wet macular degeneration can cause rapid, irreversible loss of vision.12

| For more information about the causes of macular degeneration and how it can be treated, see Macular Degeneration. |

Retinal Vein Occlusion

The macula can also be suddenly threatened by retinal vein occlusion (RVO). The retinal vein is the only blood vessel taking blood away from the eye and, when blocked, fluid builds up inside the macula, causing macula oedema.6

A world in shadow

It’s not hard to imagine how debilitating loss of vision can be – just close your eyes! You’d be unable to drive a car, watch a film or read a book. British Oscar winner Dame Judi Dench recently described her battle with wet macular degeneration – “I can’t read scripts any more because of trouble with my eyes… in a restaurant in the evening I can’t see the person I’m having dinner with”.7

By understanding how macular degeneration develops, eye researchers decided to find ways to stop blood vessels growing in the wrong parts of the retina. By stopping the growth of these new blood vessels, you could prevent bleeding, scarring and lifelong blindness. Cue the arrival of “anti-VEGF therapy”, one of the first and most successful applications of DNA recombinant technology in human medicine. We’ll look at what DNA recombinant technology is in a moment but first, what is VEGF and why is it important in diseases like macular degeneration?

What is VEGF?

When a cell gets low in oxygen, it releases a chemical signal called VEGF (short for Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) that stimulates new blood vessels to grow nearby to correct the lack of oxygen. New vessels are constantly growing all over the body in response to VEGF, even in our eyes.

But in eye diseases like diabetic retinopathy and macular degeneration, researchers realised that the VEGF system was getting a little carried away. Diabetes and macular degeneration can make cells in the retina oxygen-deprived. This meant new, abnormal blood vessels were popping up in all the wrong places, especially in the vulnerable macula. More importantly, VEGF was driving the entire process.8 Researchers needed a drug that could target and inactivate VEGF.

But how can a drug target something my own body produces?

Our immune system uses antibodies to recognise and fight infections. Antibodies are proteins bent into a particular shape to ensure they will attach themselves to a specific target, such as in an infection or a cancer. When an antibody binds to a target, it can signal other immune cells to come and destroy it.9

Our immune system has a huge variety of different antibodies for any potential invaders it might have to face. Think of your immune system as a key ring, with thousands of unique keys, ready to go for any possible “lock” it might encounter. This lead researchers to ask the question – could there be a key that could unlock VEGF?

In trying to develop a drug to trap and destroy VEGF in the human eye, researchers discovered the existence of a unique antibody in mice. This mouse antibody was the perfect “key” for the VEGF “lock”, binding specifically to human VEGF in the same way other human antibodies bind themselves to an invader. There was only one problem – would the human body accept an antibody that was from a mouse, not a human? Probably not, which is where DNA recombinant technology comes in.

This technology allowed researchers to graft a small piece of human immune protein onto the end of the anti-VEGF mouse antibody. The result? A human/mouse hybrid antibody. The mouse component could bind to the VEGF, and the human component could prevent the patient’s immune system from attacking the antibody itself.10

This groundbreaking discovery spawned a generation of anti-VEGF drugs, such as pegaptanib, ranibizumab and bevacizumab although bevacizumab is not indicated for wet age-related macular degeneration. The most common one in use in Australia is ranibizumab, approved for the treatment of age-related wet macular degeneration in 2006. It is also used for the treatment of diabetic macular oedema and for macular oedema due to retinal vein occlusion.10

That sounds great, but does it actually work?

It definitely works. Anti-VEGF drugs like ranibizumab are administered by regular injections into the eye, ensuring that the full effect of the drug occurs in the affected eye. Once injected, ranibizumab binds VEGF circulating in the eye and stops it from stimulating new blood vessels to grow. While this stops progression of the disease, it cannot reverse the damage done before the anti-VEGF therapy was started.10

In the treatment of wet macular degeneration, research has shown ranibizumab to be highly effective. In two studies, about 95% of patients receiving ranibizumab maintained their vision over 2 years, compared to 62% who did not receive it.10 Ranibizumab has also been shown to be both safe and highly effective in the treatment of macular oedema due to retinal vein occlusion (RVO), diabetic macular oedema and proliferative diabetic retinopathy.6,8

Risky business

So what’s even better than a cutting-edge hybrid mouse/human antibody treatment designed to stop the advancement of sight-threatening eye disease? Not getting it in the first place! Macular degeneration grows more likely with age and a strong family history, but there are a number of steps you can take to minimise the risk of developing it.

When it comes to avoiding or postponing macular degeneration, a healthy lifestyle is your best bet: quit smoking, get plenty of exercise and stick to a well-balanced diet. It’s not just good for your eyes, but will also reduce your risk of diabetes, which can also cause macular degeneration and diabetic eye disease. Other factors that may contribute to macular degeneration include high blood pressure and too much sunlight exposure.12

What to keep an eye out for

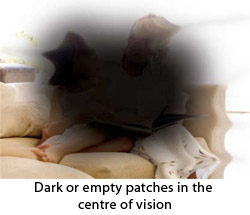

Even with a healthy lifestyle, macular degeneration can develop with age and of Australians over the age of 50, 1 in 7 will be affected by this condition.13 Patients complain of a gradual loss of visual acuity, which might first appear as difficulty reading fine print, distorted vision, blurriness or difficulty judging distances. Some people may even notice blind spots or some deterioration in their colour vision. Even if you haven’t had any visual problems, it’s important to get your eyes checked regularly. An eye examination could catch the early signs of macular degeneration before you even notice the symptoms so it is important to have your eyes checked regularly.4,12

Much more worrying is a rapid loss in visual acuity or the development of a new blind spot: These could be signs of wet macular degeneration. Any rapid worsening of vision should be attended to urgently, so see your doctor or an eye specialist as soon as possible.4

The real danger lies in brushing off the early signs of macular degeneration. If it’s caught early, the use of anti-VEGF treatment can prevent visual loss, even as the disease progresses. Ignore it, and the damage to your vision will be irreversible.

|  |

| |

Here’s looking at you!

Macular degeneration is a problem that isn’t going away, even with healthy lifestyle choices. But thanks to some pretty nifty technology, you don’t have to resort to toxic drugs, laser therapy or eye surgery to manage it.

Anti-VEGF drugs are the best example of how DNA recombinant technology is revolutionising the treatment of diseases in the 21st century. With antibody therapies like ranibizumab, we can direct our immune system to stop the progression of sight-threatening diseases like macular degeneration.

References

- Diabetic retinopathy: Symptoms [online]. London: National Health Service; 16 December 2009 [cited 16 June 2011]. Available from: URL link

- Spurling G, Askew D, Jackson C. Retinopathy: Screening recommendations. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38(10):780-3. [Abstract | Full text]

- Williams R, Airey M, Baxter H, et al. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy and macular oedema: A systematic review. Eye (Lond). 2004;18(10):963-83. [Abstract | Full text]

- Age-related macular degeneration [online]. Moorfields Eye Hospital, National Health Service Foundation Trust; 24 November 2008 [cited 11 January 2010]. Available from: URL Link

- Taylor HR, Keeffe JE, Vu HT, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Pezzullo ML, et al. Vision loss in Australia. Med J Aust. 2005; 182(11): 565-8. [Abstract | Full Text]

- Keane PA, Sadda SR. Retinal vein occlusion and macular oedema- critical evaluation of the clinical value of ranibizumab. Clin Opthalmol. 2011; 5: 771-8. [Abstract | Full Text]

- Palmer A. Dame Judi: My battle to save my eyesight [online]. The Daily Mirror; 18 February 2012 [cited 23 February 2012]. Available from: URL Link

- Guidelines for the management of diabetic retinopathy [online]. Canberra, ACT: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2008 [cited 28 February 2011]. Available from: URL link

- Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, Robbins SL. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease (6th edition). Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1999. [Book]

- Product Information: Lucentis.North Ryde, NSW: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd; 25 October 2011.

- Chiu CJ, Milton RC, Gensler G, Taylor A. Association between dietary glycemic index and age-related macular degeneration in nondiabetic participants in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007; 86(1): 180-8. [Abstract | Full Text]

- Morris B, Imrie F, Armbrecht AM, Dhillon B. Age-related macular degeneration and recent developments: New hope for old eyes? Postgrad Med J. 2007; 83(979): 301-7. [Abstract]

- Macular degeneration [online]. Macular Degeneration Foundation [cited 10/5/12]. Available from: URL Link

Dates

Tags

Created by:

Login

Login